Most of our attempts to make change rely on a belief that people can change, that change is possible. Of course, this is true—but just barely. So, this is not much of a theory of change, but rather a Theory of Unchange—a theory of why change is so hard.

Our brains are physically limited in the amount of thinking and decision making we can do; just a few hours each day is all we have.For a taste of this, watch David Rock’s Your Brain at Work. For more than a taste, drink from the deep well of Dr. Roy Baumeister. This is not a choice. This is a physical limitation, and is no more changeable than our height or eye colour.

If we were irrevocably bound by this limitation, humanity would literally still be shivering in caves. But instead we have developed coping mechanisms that allow us to recycle past decisions so we can use those few daily hours for new problems—as well as for the quotidian minutiae of life.

These coping mechanisms include: habits, rules of thumb, laws, social conventions, religious strictures, myths, superstitions, writing and publishing, social structures, governments—and especially physical infrastructure.

That I say “especially physical infrastructure” signals my bias. But I am a designer of products and systems, so rather than bias I like to think of this as my special insight.

We say, “like a fish in water” to draw attention to something that is so taken for granted it cannot be seen. But the fish is probably aware of temperature, density, salinity, taste, smell, and currents—without naming these things as properties of water. And so with humans. We are aware of wide roads, narrow roads, bumpy roads and smooth roads, but we seldom ask Why Roads? Or what would happen if roads were different.

Roads are something that many of us interact with regularly, perhaps for several hours a day, and some of us spend some of our few conscious hours thinking about them. But what about the things we are less aware of, like the insulation in our walls, the method of generating our electricity, or the type of piping that irrigates our food?

The way our electricity is generated can lock in orders of magnitude more pollution that we can ever affect by turning our lights off. The way our cities are built can lock in order of magnitude more pollution than we can affect with personal driving choices. We built these systems to cope with our limited ability to pay attention—to think and choose. Changing systems is the most powerful lever we can pull.

Of course, everybody knows this—people who care about these things sagely nod over Donella Meadows’ essay on leverage points. If she had known about recent brain research that shows how little conscious thought we have, Meadows probably would have been even more insistent that we focus on systems. And yet, probably because system change is so daunting, almost without thinking we default back to advocacy and education for personal changes—the same finger wagging about light switches and shorter showers that we know does not work.

We say these tactics aren’t working—and that implies that they could work, if only we did them better, or bigger. Better framing, more fundraising, better creative, more crowdsourcing, viral this or that.

But it is not that they don’t work, it is that they can’t work. They can not work.

Attention is a physical resource, which means our attention is exhaustible—in fact, it is very easily exhaustible—and finite. This means fighting for attention—as we do with our campaigns, social media, and documentary films—is a zero sum game. Attention is a limited commodity, and when you use it, it is gone. It is not that the tactic needs to be bigger, it is that the attention is already used up—gone.

This means this sort of work is fundamentally competitive. In order to succeed, something else must fail.

If you are going to get attention, you must take it from somewhere else. Essentially, you must stab your friends in the back. If your friend has a cookie that you want to eat, there is no amount of community engagement that will make that cookie multiply. You can take the cookie from them or share the cookie with them, but either way, your friend gets less cookie.

This may not be bad when we are talking about cookies, but when we are talking about medical research, food aid, endangered species, climate change, social justice, addiction…you are taking the cookie from some very important issues. Furthermore, these issues are already fighting for brain space against work and family and television and magazines and facebook…

Now, some very smart academics who study these things think that 80-95% of our behaviour is determined by the context we are in.I think the most interesting work is by Dr. Sandy Pentland—and I think the most important work for organizations and changemakers to wrap their heads around is by Dr. Alex Bentley. I think these smart academics are like fish, and so can’t see the water they are swimming in—the physical context. They don’t see the way our behaviour is profoundly shaped, not just by roads and plumbing, but by building codes and zoning regulations and trade agreements.

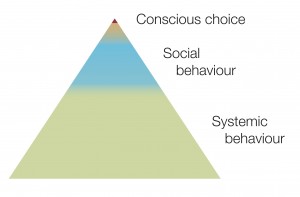

One researcher thinks 99.999% of our behaviour is shaped by our context, and I think he is much closer to the truth. I developed this pyramid model to show what my hunches of the relative sizes of behavioural influences are.

So, we should start by asking how we can change the system. Only after we have relentlessly eliminated any hope of ever changing the system should we try to fight for attention. If you can’t change the system, most of the time it would be better to do nothing at all rather than rob attention from an issue that has a chance. Fighting for attention is our last gasp, the thing we do when we are convinced we have no choice and our issue is so important we are willing to stab our friends in the back in order to steal attention from the issues they are working on. And even then, we will probably fail.

If we truly want to make change, we must stop asking for attention; we must work on the system. We need to look for the way to educate the fewest people—just the right people, the bare minimum needed to create the change we seek. We must build compassionate systems—systems that make our desired behaviour as effortless as turning on the tap or flicking the light switch.

We must build water.

Hi Ruben – thanks for pointing me to this. I’m largely in agreement with you. Attention is limited and there’s often a poor (or entirely missing) link between what we “know” and how we behave. And absolutely systems and physical infrastructure almost always lock in behaviour and associated pollution far greater than we can influence through personal choice around how we use that infrastructure. I say almost – the personal choice of many Londoners to commute by bicycle has resulted in the building of the cycle-superhighways in London which in turn have multiplied the number of people cycling – the majority of people will not cycle to work in London without protective infrastructure which would never have been built without the prior personal choices of many. A small victory whose example is probably not applicable in many other situations.

I’ve just downloaded the Meadows essay but I’m interested in the intersection of leverage points and attention. During the civil rights clashes in America in the 60s there was an incident where Martin Luther King marched into a town because he knew that the local law enforcement would over react – it was a very definite move to focus attention. In fact I can’t really think of any real change that hasn’t required the focusing of attention in some way on the problem. I guess this can come from two sides – one can focus peoples attention on something in such a way as they come to believe that its no longer acceptable – or you can focus the attention of those engaged in some action by making it to expensive for them to continue.

Perhaps with sustainability the issues are too diverse and there’s no single point on which one can focus – climate change perhaps worked as that point for issues of sustainability for a time – and then the very word sustainable was co-opted by the system – so sustainability in the face of climate change came to mean sustaining growth by investing in green technology.

I feel like I’m heading down a rabbit hole so I’m going to stop writing – before I do I have a question – where would you focus attention if you could?

Bruce, I apologize—I just found your comment in an unexpected comments folder.

Your London example should be our default strategy: A small group of people expends great focussed attention. First they demonstrate personal change, then they demand system change so everyone else does not need to expend such effort.

As far as MLK… these are the big examples we tend to think of.

But who marched for drain traps on our sinks and toilets to keep sewer gases out of our homes?

Who marched to have intermittent settings on our windshield wipers?

Huge amounts of our behaviour is shaped, changed, modified, controlled, determined by very few people.

Yes, those people are paying attention, but this should be another default strategy—try to think of how to create change by having a meeting with fewer than six people.

Is a street march really the way to change the building code? First off, how many people will march to change the building code? Second, are the people in control of the building code paying attention to street marches? Especially tiny and quiet marches as would come out for the building code?

There are a small handful of people who control the building code. We need to focus on them, not on big public education campaigns.

As you say, sustainability is a big and complex problem, which, as I discuss elsewhere, I don’t think we are going fix with a society that looks like this one. But I think there is still plenty to do.

So here is what I wrote with my suggestions on where to focus attention.

At the end of the world, there is plenty to do.

Thanks for your patience, and I am sorry for the long delay!

Ruben.

[…] Maybe it just doesn’t work.2 Maybe we need to do something different. […]

[…] The Compassionate Systems Theory of Change […]

[…] The Compassionate Systems Theory of Change […]

Interesting approach, Ruben. And I heartily agree that a much more concerted effort to understand and work with systems needs be made by individuals and communities, if we are to effect real and lasting change.

I find Baumeister’s approach to “ego depletion” and losing attention to be shaky. Always have. And now a majour paper suggests the same thing. If this paper is correct and Baumeister is wrong, then, perhaps, creating and sustaining change may not be as hard as you suggest. Especially if we get a better handle on systems and structure and how they influence and change behaviour. Yours in curiosity!

http://www.slate.com/articles/health_and_science/cover_story/2016/03/ego_depletion_an_influential_theory_in_psychology_may_have_just_been_debunked.html

Thanks for reading Bruce. And yes, I have been watching the critique of Baumeister with interest.

But Baumeister merely says we are more limited than we think. David Rock puts our conscious, focussed attention at a few hours. Kahneman wrote “Attention and Effort” in the 70s. Tor Norretranders wrote about this in The User Illusion.

And, we all have the direct experience of feeling like our brain is mushy after a hard day of focus.

Say all of these people are wrong, and we don’t have 3-4 hours of focussed thought. We actually have….the 16 hours we aren’t sleeping. So we have increased our capacity by four or five times! Huge!

And still utterly incapable of accomplishing the tasks, if the tasks we set are conscious, focussed uses of attention. There are simply too many issues that require too much time and effort, not to mention we still need to make a paycheque and maintain our relationships.

So, while Baumeister is a great reference, the argument easily stands without him.

Incorporating our physical limitations into governance and policy is the first step. This means democracy as we tell stories about it is non-functional, so I am in favour of radical implementation of Citizen’s Assemblies.

And systematize, systematize, systematize.

This article was fabulously written, It takes away the frustration, of shouting to a deaf society. It makes me feel, I am not alone. I am living in a country, that is facing the worst water crises in its history, and the situation is not reaching even a fraction of the population. We are one of very few countries in the world that, can still drink water from a tap. So, responsible and sustainable usage of the precious source, comes way down the “to do list”, most of the population.

I am glad this was helpful for you Fifi. Best of luck fighting the battles in your area.

I like this, thanks! Yes, let’s build them. Maybe what really matters is, before we get to “educate the fewest people” as you say, we need to get the attention of some few people who are ready and willing to collaborate with us, as we are with them.

I’m (very) slowly building a system to do that. People are welcome to help 😉

Thanks for reading Simon.

There certainly are very few large systems we can change by ourselves; we generally need to get the attention of other people to have impact.

But I think we may be surprised by how few people we need…

When I was working at the City of Vancouver, there was a staffer named Dave who was in charge of green building policy. He slowly rewrote Vancouver’s building code, and, because Vancouver was so far ahead and had done so much work, the Province of BC largely adopted Dave’s work. So Dave changed the system for four million people.

Not every system may have a Dave, but I bet more do than we can ever imagine. We should try to find our Daves.

[…] The Compassionate Systems Theory of Change […]

[…] The Compassionate Systems Theory of Change […]

“building water” is a brilliant metaphor for “seeing” consciously that fluid in which systems and self are suspended and when one sees the toxicity of the fluid though still able to suspend the self and the system, then one realizes the task at hand. We must build [new] water.

I am glad you like the metaphor, Dave. I must say, it was suggested that I cut that phrase and find a different way of saying it—but I liked it too much.

Cheers,

Ruben.

I really like this. It makes a lot of sense. The question is, how can an individual get the attention of those who can pull the lever? What chance does the average person have of actually being able to do this? Right now it seems like giant entities are pulling all the levers and don’t really care about the impact, except to their bottom lines.

Thank you for your question, Carren, and I am sorry it took me a few days to respond. I think your question is so important I wanted to be able to sit at a real keyboard with a large screen.

It is a very important question, and I don’t think it has an easy answer—at least the answer isn’t easy to hear. I think you are right. There is very little chance of an individual getting the attention of those pulling the levers.

So stop trying. Do something else. As I always say, “When in doubt, grow beans.”

Of course it is a little more complicated than that. We see examples of individuals, small groups, and even large campaigns working, every day, all around us.

But what is the scale? If a handful of projects work, can we solve the problem just by multiplying the same tactics by a thousand times? I think this research says no. I think the research shows we will never get more than a handful of projects into the public attention. Which leaves us with 9,995 more projects, starving for attention.

Again, if what you are doing doesn’t work, the answer is seldom to do the same thing bigger and faster and louder. The answer is to do something totally different. Look for the third way, and the fourth way, and the fifth way.

And, we may just not get what we want. We should probably focus on what we need.

Great article! Maybe the answer is to ignore the rarified world of “lever pullers” I think you nailed it suggesting we concentrate on the detail people: the working-level technical CivilServants like your friend Dave that piece by piece, translate the budgets released by ‘lever pullers’ into daily, tangible reality.

I am glad you liked this Joseph.

So love this Ruben. . . . . would love to help build water . . . .

Thanks Nicole!

Thanks for your article! Don’t you think that first we need to get attention for a change of our conscious choices and social behaviour (to adopt more sustainable practices) to let people realise that these often cannot be adopted due to incompatible systemic behaviour?

How will you encourage systemic behaviour otherwise? Governing institutions will not change by themselves, I am afraid.

Thanks for your comment Robert.

I would like to give it a good answer, which I might not be able to do for a couple of days. Stay tuned–

Hi Robert,

Most of our impact is neither conscious nor social, or if it is, it is not a necessary part of the behaviour.

For example, two of the largest environmental impacts our society creates are from heating buildings, and transportation.

Let’s break these down. We don’t heat buildings because we desire to create climate change, or because we love spending money on utilities. We heat buildings in order to be comfortable. This can be accomplished with better building design, proper siting, and insulation and draughtproofing. PassivHauses may not require heat at all.

Now imagine you rent an apartment, and unbeknownst to you, the building is built to the PassivHaus standard. Several months later, you may wonder why you are not getting a utility bill. But will you be outraged? Will you demand to pay? No. We pay because the system forces us to pay, not because we made a conscious choice to pay.

Similarly with transportation impacts. These are largely determined by zoning regulations that enforce sprawl, and separate living from working and shopping. In cities with traditional urban form, the impact of transportation is much smaller.

Some people are beginning to choose to move into traditional urban areas. But what we want is to remove that choice, by simple requiring that cities be built in ways that do not require climate-changing transportation. We want people to be born and live in walkable cities, so that they never consider they might need a car to drive around.

Try just letting your eyes go out of focus (metaphorically) and try to see the system design that shapes behaviour before you look for the social and conscious behaviour. How does the chair you are sitting on shape you? How does the room you are in affect the conversation you are having? How is your physical environment constraining the options you can even bring up for consideration?

As we talk about shaping the physical context, I think it is important that we recognize that most regulation is not political, or has a very limited political touch. In the case of building codes, the code is written by bureaucrats, usually very few bureaucrats. These folks are much easier to contact and influence than politicians. Worst case scenario, the building code is voted on by politicians—but even that would be a vote to accept the recommended changes to hundreds of pages of building code—they are not going to drill down into the specifics of caulking and insulation.

I hope that answers your question—please reply if I have muddied instead of clarifying.

Best,

Ruben.

This is insightful stuff…depressing and disheartening but great. I am a fellow SCORAI-er and reached it that way. Thank you for sharing.

I am glad you like it Jeanine. It sure can be depressing, but I think this lens gives us the opportunity to focus our work very sharply. Cheers.

Great post & diagram. Thank you for writing. Shared on FB.

*The last sentence (unless I’m misunderstanding something): I’d say “water” [energy / nature] already exists, free of need to build it, but yes, we simply need to (create systems so that we) live more easily in flow with it. We need to *be* water (perhaps?).

Thanks for sharing this, and for thinking so deeply on this.

The last sentence is a bit of leap, isn’t it? I was trying to allude to the notion that we need to build systems such that they are as unseen to us as water is to a fish.

I will thresh it a bit, and see if there I can tweak it for more clarity.

I like the “we need to build water…” metaphor, and I would not change it. Water is a system whose composition, structure and flow shape its inhabitants – and – which is incorrectly taken as a given. How better to convey the taken-for-grantedness of systems — AND the mistaken notion that our systems are “natural”?

Good points–thanks for your thoughts.

No need to respond – but the old water in a goldfish bowl metaphor is perfect for the way humans imagine our environment vs. the reality. A related thought experiment I like to play with is asking people in cafes: “If Earth was 10 feet across – say the height of this room – how high would the biosphere be relative to the 10 feet? Many people guess 1-2 feet. The truth is more like a millimetre. Which is shocking ot most people. And it allows us to see much more easily how our impacts are part of our biosphere, not separate. Would be interesting to do a 10 foot model of this.

That is a grabby metaphor all right. I have heard descriptions like the relative thickness of the biosphere is like the coat of paint on a globe.

But to share this metaphor with people you must get their attention, and that puts right back in te cognitive capacity problem. Even Al Gore’s wildly successful talk, movie and tour did not reach more than a fraction of the population.

But yes, when you are talking to the gatekeepers of the system, I think that is a very visceral model.

A wonderful, and insightful, read. I would simply suggest changing the metaphor in the last sentence; indeed, “green” buildings have to resort to automatic lights with motion sensors and timers, precisely because flicking off the switch requires attention and most people are simply not attentive enough to do it for the reasons you mentioned. Maybe it’d be better to say: “as easy as turning on the TV or scrolling through Facebook”. That really conveys the behavior of the automatons we all are during most of the day.

I am glad you liked it Emmanuel, and thanks for your suggestions. I have built a strong habit to turn off light switches, but the example falls apart for people who haven’t!