We are swamped with requests—seductions—for our attention. Most of these will fail, and if you are in the business of changing people—say you work for a government or non-profit—most of your work will fail too.

This is because change hurts.

Behaviour is hard to change, and we make it harder by ignoring basic facts of behaviour. The most ignored fact is that our brain has limited attention. We often say your brain is a muscle, but even a well-fed muscle has limited capacity. And just like a muscle, no amount of energy drinks or gels will allow you to work, play—or think—indefinitely.

If we spend our attention on cute kitten videos instead of endangered spiders, then that attention is gone for now. Most change campaigns ask for attention, and so they fail.

So failure to create change is mostly because we are thinking about change wrong. It is not because people are apathetic or stupid, or because the communications are bad or change isn’t fun! It is just that when we choose to fight for attention, we choose to fail.

Success requires changing the approach. We must work with people—and their brains—to build new systems that support different behaviour. I call these Compassionate Systems.

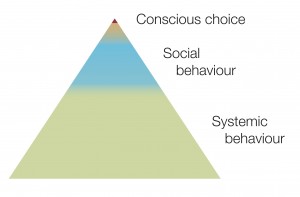

Compassionate Systems are necessary because our behaviour can be roughly divided into three arenas, shown here as a pyramid. Conscious Behaviour is just the tiny tip, Social Behaviour is several times larger, and the vast majority of the pyramid is built of Systemic Behaviour.

So while most of our behaviour is determined by the systems we live in, our current systems are often not built for us—like suburbs with no sidewalks, built for cars, not for people. Compassionate Systems are built for real human beings, built to support us so we can do more.

We need the support of Compassionate Systems because we humans are beautiful—and flawed. Our flaw is we think our mind controls our behaviour, but in fact we are social creatures, not rational.

We have built a world—we have built our systems—for the rational person, not the real person, so we have built a world that hates us. We have built a world with infinite hot water, and then we are blamed for taking long showers. We have built a world with wide highways and fast cars, and then we are blamed for driving too much. We might as well blame the giraffe for eating leaves from the top of the tree.

Rather than blaming us for not caring, compassionate systems recognize we can only do so much. If we are to be effective against climate change—or the other critically important social and environmental issues—we must build a world that loves us, a world that accepts our limitations.

Compassionate systems accept human limits, both physical and cognitive. They are user-centred and based on observation and testing. We see them all around us—every car comes with a seat belt, it is not an extra feature you must pay for. Lead was removed from paint so people didn’t have to debate the pros and cons of painting their child’s crib with lead or lead-free.

If you want people to recycle more, you can tell people to buy a recycling bin, and then, if they don’t recycle, you can complain they don’t care. The compassionate system gives them a recycling bin, but more importantly, the system innovates to eliminate packaging so people don’t need to recycle—the recycling bin signals system failure. The compassionate system regulates fisheries so people don’t need to spend attention at the fishmonger, green labelling systems signal system failure. The compassionate system builds Net Zero homes, energy feedback displays signal system failure.

There are thousands of important issues that need our attention, and thousands of businesses that want it. Our attempts to create change often carry an undercurrent of blame—You need this app because you are lazy; We need better sound bites because you don’t care; You need this website because you are ignorant—but the data shows people aren’t the problem, bad systems are.

Though we tend to act like our brain is infinitely capable, Dr. Roy Baumeister has found we have actual, physical limitations to our attention, analysis and decision making. Just like you can only run so fast and jump so high, you can only think so much. We have evolved ways of conserving our brain resources by filtering information, using rules of thumb and building habits. But even still, we can only do so much.

So, failure to capture attention is not necessarily because your work has poor communications or is disengaged from the audience; it is likely your audience is just spending their limited attention elsewhere. This means if you successfully get your audience’s attention they cannot give their attention to something else—climate change at the expense of overfishing; aid for hurricane victims at the expense of cancer research. Success on one issue means you are stabbing other important work in the back.

The key is to stop asking people to pay attention, because paying attention exacts a literal cost. Stop using the finite resource of attention, and start drinking from the deep wells of Social Context and especially System Change. A few simple rules allow birds to dip and swirl in beautiful rhythm—clearly we must find the rules for environmental behaviour that birds have for flocking;

Dr. Michael Gazzinaga says, “Probably 99.999 percent of what goes on in the brain is automatic and unconscious.” MIT’s Dr. Sandy Pentland thinks 95% of behaviour is social, and Dr. Alex Bentley has shown how the mode of social transmission can seen in the shape of the graph of transmission over time.

So good framing and communications can help increase the effectiveness of that 1-5% of our behaviour that is consciously chosen. Community engagement and social norms start to work on the 95% of our behaviour that is socially determined.

That neatly adds up to 100%. But we have forgotten about the system.

Our flaw is we think we are rational, but we are social creatures. But society itself is built on and within the choices of hundreds and thousands of years. And so, most of our behaviour may be thought of as being neither rational, nor social, but systemic—the behaviours are determined not by conscious choice, nor by the peers we engage with, but rather by the world we have built.

From the littlest things like how high the light switches are in your home to the biggest things like energy generation or international trade laws, much of our day-to-day behaviour is locked in by the system we live in. In explaining the design of the International Space Station, Jim Plaxco tells a fascinating story of path dependancy, tracing through NASA, Victorian train rail gauges, the Roman Empire, and finally to pre-Roman history, only to find the determining factor is the hindquarter width of draft horses.

So how much of our behaviour could be locked into the system? Dr. Robert Ayres studies Industrial Metabolism and finds, on average, 94% of material never makes it into the finished product, it is consumed or discarded in manufacturing. So, when we try to communicate, engage, or change the choice architecture around recycling, we are still only affecting 6% of the material.

Does this mean 94% of our behaviour is determined by the system? Does this mean our conscious and social choices are only 6% of our behaviour? Obviously the correlation is not going to be so neat and tidy, but just as obviously, we must go upstream. Donella Meadows eloquently told us the power of system change, and the even greater power of paradigm shifts.

System change is not smart meters or video gaming energy conservation—those tactics may be more effective than current outreach strategies, but they still demand attention; therefore, they can only work in the tiny arena of conscious behaviour and the small arena of social behaviour.

Choice architecture does change the system to exploit our cognitive limits, but we must still be aware of how far upstream our choice architecture reaches. Altering choice architecture can, for example, greatly increase the choice of healthy meals, but the diners largely will not, and cannot, make choices to affect the farms upstream of their dinner. The choice architecture changed behaviour in the dining room, but not on the farm—the lettuce may be doused in pesticides and harvested with forced labour.

So, understanding the scale of the three arenas of behaviour; Conscious, Social and Systemic allows us to draw a few conclusions:

- Changing systems will have the greatest impact

- We must be very strategic about who we ask to think and what we ask them to think about

- We must be very skilled in how we ask them to think

- We must ask them to think about changing the system

- Asking them to think about their own behaviour should be a last resort

By understanding the scales of the arenas of behaviour change, we can greatly increase the effectiveness of our work. This simple pyramid model can help us identify what arena we are working in, and can help us question the assumptions keeping us in that arena rather than working in a larger and more effective arena. The pyramid model dramatically and clearly illustrates the challenges of certain strategies and offers motivation to work in other ways.

[…] you to watch my video, The Top Ten Myths of Behaviour Change, and then follow it up with reading Compassionate Systems. Or, you can rely on the opposition to hold them to […]

[…] would a better strategy be? I think we must build Compassionate Systems that shape our behaviour or address problems without needing attention. A programmable thermostat […]

This is a fantastic post. You posted a link on the Victoria Sharing Economy Facebook page, and I fell down the rabbit hole of your website. It’s great!

With your permission, I would like to use this post in a class I teach (sometimes with Jeremy from the Victoria Sharing Economy site), where we have the students propose ways to reduce the number of single occupancy vehicles that come onto our campus. I think this article might help them think about what might actually drive behavioural change…

I am so glad you find this useful, Amy. Please do use it in class—I will send you a very recent version from a new angle as well. Let me know if you would like any details filled out or citations.

Cheers,

Ruben.

This explanation of why we’re dysfunctional when it come to stopping civilization-destroying climate change was somewhat helpful in one sense, i.e., the “ah-ha” sense. (I was blaming, and still do blame, human nature for some of it.) But, and I know it’s too much to ask, I don’t see this getting us much closer to salvation:<!

Well, salvation is a pretty tall order. But, I think salvation is impossible if we try to achieve it using false models, like education changes behaviour. With a more functional model, we have a better shot at salvation.

And, I think there are lots of worthwhile things that might not be seen as salvation, but that are important—things like urban agriculture, home weatherizing, walkable neighbourhoods. I think we will have a much greater chance of accomplishing more good things if we are using good models. So, we may not achieve salvation, but we could have nice, fresh, local salads. 😉

And have you seen my post on salvation? https://smallanddeliciouslife.com/i-dont-want-salvation/

Well this is very cool. Thanks for this. I saw your post on Tzeporah Berman’s FB feed. I work in behaviour change – albeit through theatre and multi-media – so I know a few things about attention and change. And I know Angus and Tad, (a little) so I feel so IN this story it’s not funny. 🙂

We’re right with you here. At DreamRider, we’ve been developing a program, the Planet Protector Academy, to utilize the power of kids to change their families’ behaviours on energy and transportation through an immersive game experience in class. We create a little feedback system where the children learn to lead change in their families over time, nudging their behaviour. We’ve been getting 49% of the families to drive less, and 76% of the kids to take shorter showers.

I loved your comment to Jenny because her problem is our problem: when you have a hugely innovative program, how to communicate about it effectively? And I love your ‘funnelling’ approach, which is something we’ve been considering: find a large eco non-profit with teachers already on board, who is looking for a product like ours and can ‘funnel’ teachers to us. Fabulous!

I love your red dot solution, this is completely up my alley. I’d love to keep hearing more about your work, and if you’re interested in hearing more about mine, let’s have coffee!

I am so glad you like this Vanessa, DreamRider looks very cool as well. Please do go to the sidebar if you would like to sign up for email updates.

The challenge we face is that we are only using one tool to solve all our problems—education and awareness.

So, we need to educate kids about safe sex. Great! let’s hire DreamRider! And now we need to educate kids about recycling. Great! let’s hire DreamRider!

The problem is there are ten thousand critical issues—poverty, inequality, climate change, schools in Afghanistan and clearcutting in the Amazon, and on and on and on. If we used outreach for all of those, people would be spending their entire lives inside a theatre—which would at least help lower consumerism because they would have less time to shop.

And of course, only half of your families are driving less. Not quitting, just driving less, and only half the families. Is that because the others don’t care? Because they are stupid, or worse, hateful? Is it because you are bad actors?

I don’t think so. I think it is because we have built a system that requires driving. We live far from our work and our groceries. It takes a real freak to overcome that—which is why there is so much room in the bike lanes.

So I think our education and our campaigns must be focussed on changing and creating different systems. I would like someone to commission DreamRider to work on walkable neighbourhoods. We shouldn’t be talking about buying locally, unless it is part of a strategy to require local sourcing. Don’t work on shorter showers, work on changing the building code to apply a maximum energy usage per square metre.

We need to save our energy to think about things that truly have no systemic answer. We need to save our energy to apply at parts of strategy that leads to system change. I bet there are lots of times you would like to get into much meatier issues—more systemic issues—with your work, but are limited by groups that think “it is all about education”.

Anyhow. Best of luck to you in your work. Keep drilling deeper!

Fascinating, thank you! I’m a writer for Watkinson School (www.watkinson.org), a unique independent school in Hartford, CT. For many years, we’ve been struggling with effectively “selling” the school, precisely because what we’re selling is a school that does things differently (and better!)—a change to the system. (In short, we focus on teaching creative as well as critical thinking; on learning about HOW each of us learns best in order to maximize our potential; on shaping our own lives and the world around us, rather than just “getting into college” or “getting a good job.”) Potential families don’t even understand, really, what we’re doing, because it requires a shift in seeing and thinking about what education is and can do. My job is to articulate our unusual approach, but I have not been as successful as I’d like to be. I see now, after reading this elegant article, that right now our efforts merely compete for limited attention, rather than changing the system without need for anybody else out there to do anything. My OWN brain feels a little wrenched at the thought of trying to conceptualize a new way of acting, rather than just writing new marketing copy… but I’m inspired! I’d love any advice that comes to mind, or suggestion for further reading. The red-dot example in the comments above was helpful. Thank you, thank you! ~Jenny

Hi Jenny, I am really glad this was useful for you.

Well, I guess the system approach might be to change the system so students are just automatically funnelled to you. I don’t know if you have any chance of that.

But, it is fair enough to look at this as a straight marketing copy problem, for a few minutes anyway. Anybody that comes to your site has already decided to give you some attention, and so you need to get very good at maximizing that before they bounce off the page. I would do some very, very sensitive polling of the people who do not send their kids to your school.

By sensitive polling…my mind was blown by the pollster Angus McAllister, who told me you never ask someone if they like the colour red. You show them a picture of a guy in a red sweater, and then ask them how they feel about the guy. Then you show a different group a picture of the same guy in a blue sweater and ask them how they feel about the guy.

The marketing coach Tad Hargrave says too much marketing is about the boat, how great the boat is, how powerful it is, how nice the cabins are, how shiny the bar is. But what travellers want to hear is about the island. How will I feel when I am on the island? What will being on the island do for me? Who will I be after visiting the island?

So I guess that sounds like you shouldn’t talk about the school facilities and programs. Talk about who the students will be after their education.

Then, and I am sure you have thought of this, so I will just say this to reinforce your thinking…if you can pre-select for the people who are better primed to pay attention to your communications, that would be great. Activating alumni seems critical. Maybe try to get employers of the kids, even if they are just working at a burger stand, to proselytize for the school. Are the most capable kids in jobs, arts, volunteerism coming from your school? Then try to get the people who are working with your students to be your recruiters.

Good luck with this. It sounds like you have your work cut out for you.

Can you give examples of this strategy and how it works? I understand the concept, but how can it be applied? Too much theory not enough instruction for application and I’m not exactly sure how to use the pyramid. Otherwise I’d love to apply to my work.

What? Theory isn’t enough for you? You want this to “work”?

Hmph.

In this article, I am trying to do a couple of things. I am trying show why the old way is not working. It is very important we stop wasting time, energy, money, and most importantly, audience attention, on things that don’t work.

And the second thing is to show how systems just make things happen. Now—this is not news. Everybody who works for change knows system change is best—but it is hard to achieve, so they often give up and go back to comfortable old things that don’t work. My favourite article on systems is Leverage Points, by Donella Meadows.

Furthermore, system change often requires old-style campaigns. I point out that cars just come with seat belts now. The system is changed so everybody has access to a seat belt. But that didn’t just happen, it took advocacy, media, communications—all the usual campaign stuff.

The question is, can we change the system without a campaign, in which case that should be our first and only goal. If we cannot, we must campaign for system change—any hopes that education and awareness will create some sort of new consciousness resulting in everybody just being nice is a waste of your life. The campaign must have a laser focus on the end result of system change—not, as I discussed above focussed on regulating people, but rather on regulating the system.

And, what if there is a middle ground? Have you heard of the Red Dot? In Canada, if you don’t want junk mail, you just stick a red dot sticker on your mailbox. That tells Canada Post to not bring you junk mail. Now, a website started promoting this, and selling inexpensive red dot stickers. They got tons of media—hundreds of news stories.

But when I was testing behaviour change interventions, I walked into an apartment lobby that had no red dots. 50 units and not a single red dot, despite what looks like a very successful campaign (If you listen to my slidecast you will hear the sad results of similar results concerning ethical seafood wallet cards).

So, I stuck up the red dots. I changed the system. (You can read a very old version of this test here). Every time I have done this or heard from someone who has done this, there has been an 80-90% uptake. From ZERO to NINETY PERCENT SUCCESS. With a paper red dot sticker.

That is a compassionate system. It recognizes that people do not have the brain space to learn about red dots, find a red dot, stick up the red dot. The compassionate system just puts a red dot on their mailbox, and if they want junk mail, they can peel it off.

It would be ideal if the Government of Canada would just ban waste, but that level of system change looks unlikely at this point. So you can do it. Any time you go to a friends house or apartment, put up red dots. Or maybe this could be a school project. A competition in Scouts—how many apartment buildings can you hit.

And this is the sort of thing environmental groups should be doing. NGOs should not waste even one more second blathering about how people should just say no to junk mail, they should just spend that time sticking up red dots. That has a real result of reducing wasted paper.

I hope that will clarify some details. If you are working on a specific topic, please post some details for brainstorming.

Leverage Points can be found at http://www.donellameadows.org/archives/leverage-points-places-to-intervene-in-a-system/

Thanks so much for posting that Mark, I don’t know why I didn’t link it in the first place—I’ll go add it to the article.

The .pdf version that I use can be found at http://archives.evergreen.edu/webpages/curricular/2006-2007/ecobuild/files/ecobuild/Leverage_Points_0.pdf

Wow this is amazing! Rarely do i read something that looks at problems in this manner. Great job and thank you for writing.

I am glad you found it useful, Kaleb. Keep checking back, or sign up for occasional emails, and I will update you as I keep fleshing this idea out.